Serial Computing

Traditionally, software has been written for serial computation:

- Run on a single computer

- Instructions are run one after another

- Only one instruction executed at a time

Von Neumann Architecture

The Von Neumann architecture has been the basis for virtually all computer designs since the first generation.

- John von Neumann first authored the general requirements for an electronic computer in 1945.

- Data and instructions are stored in memory.

- Control unit fetches instructions/data from memory, decodes the instructions, and then sequentially coordinates operations to accomplish the programmed task.

- Arithmetic Unit performs basic arithmetic operations.

- Input/Output is the interface to the human operator.

Von Neumann Architecture - Components

- Main Memory

- Store program instruction and data

- Program instruction – code to instruct computer

- Data – information to be used by the program

- I/O Equipment

- Central Processing Unit (CPU)

- Arithmetic Logic Unit

- Control Unit

- Fetches instruction/data from memory

- Decode instructions

- Sequentially coordinated operations to be performed

Processor Registers

User-visible registers

- Minimize main-memory references

- Referenced by assembly language instructions (i.e., not high-level languages)

- Types of registers

- Data - can be assigned by the programmer

- Address – used for direct or indirect references to main memory

- Condition Codes or flags

Control and status registers

- Control operation of the processor

- Control execution of programs

- Program Counter (PC): Contains the address of an instruction to be fetched

- Instruction Register (IR): Contains the instruction most recently fetched

- Program Status Word (PSW): condition codes; Interrupt enable/disable; Supervisor/user mode

Limitations of Serial Computing

- Limitation of single CPU

- Performance

- Cache memory

- Transmission speeds

- The speed of a serial computer is directly dependent upon how fast data can move through hardware. Absolute limits are the speed of light (30 cm/nanosecond) and the transmission limit of copper wire (9 cm/nanosecond). Increasing speeds necessitate increasing proximity of processing elements.

- Limits to miniaturization

- Processor technology is allowing an increasing number of transistors to be placed on a chip. However, even with molecular or atomic-level components, a limit will be reached on how small components can be.

- Economic limitations

- It is increasingly expensive to make a single processor faster. Using a larger number of moderately fast commodity processors to achieve the same (or better) performance is less expensive.

Parallel Computing

- Simultaneous use of multiple compute sources to solve a single problem

- Use of multiple processors or computers working together on a common task.

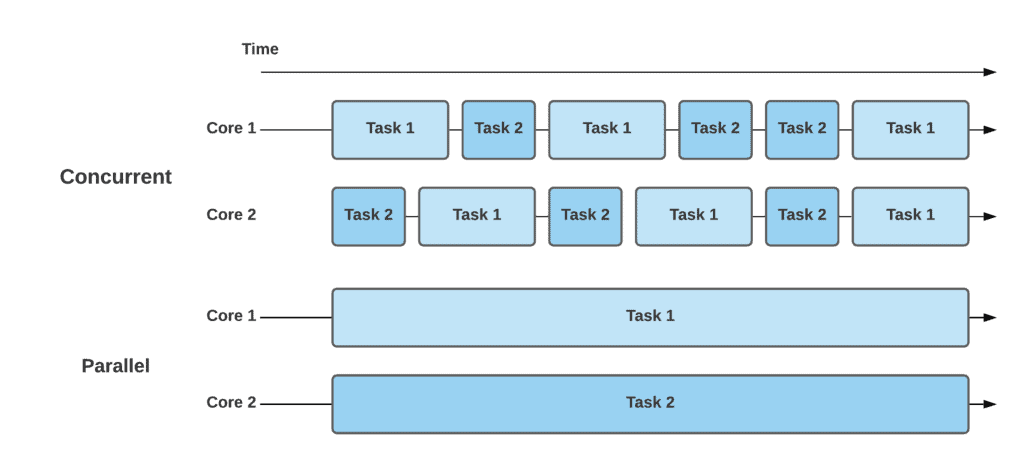

Parallel vs. Concurrent

- Concurrency (switch contexts) actually means that multiple tasks can be executed in an overlapping time period. One of the tasks can begin before the preceding one is completed; however, they won’t be running at the same time. The CPU will adjust time slices per task and appropriately switch contexts. That’s why this concept is quite complicated to implement and especially debug.

- Parallelism (simultaneous) is the ability to execute independent tasks of a program in the same instant of time. Contrary to concurrent tasks, these tasks can run simultaneously on another processor core, another processor, or an entirely different computer that can be a distributed system. As the demand for computing speed from real-world applications increases, parallelism becomes more common and affordable.

What is Parallel Computing?

In the simplest sense, parallel computing is the simultaneous use of multiple compute resources to solve a computational problem. It can be run using multiple CPUs. A problem is broken into discrete parts that can be solved concurrently, with each part further broken down into a series of instructions. Instructions from each part execute simultaneously on different CPUs.

Parallel Computing: Resources

The compute resources can include:

- A single computer with multiple processors

- A single computer with (multiple) processor(s) and some specialized computer resources (GPU - graphics processing unit), FPGA - Field-programmable gate array, etc.

- An arbitrary number of computers connected by a network

- A combination of both

Characteristics of Computational Problem

- Broken apart into discrete pieces of work that can be solved simultaneously

- Execute multiple program instructions at any moment in time

- Solved in less time with multiple compute resources than with a single compute resource

Importance of Parallel Computing

- Ability to solve larger problems

- Ability to solve the same problem faster than the single CPU

- Provide concurrency (do multiple things at the same time)

- Limits to serial computing

- Taking advantage of non-local resources - using available compute resources on a wide area network or even the Internet when local compute resources are scarce.

- Cost savings - using multiple “cheap” computing resources instead of paying for time on a supercomputer

- Overcoming memory constraints - single computers have very finite memory resources. For large problems, using the memories of multiple computers may overcome this obstacle

Limitations to Parallelism

- True data dependency

- A data dependency in computer science is a situation in which a program statement (instruction) refers to the data of a preceding statement.

- Procedural dependency

- Resource conflicts

- Output dependency

- Anti-dependency

- An anti-dependency, also known as write-after-read (WAR), occurs when an instruction requires a value that is later updated. In the following example, instruction 2 anti-depends on instruction 3 — the ordering of these instructions cannot be changed, nor can they be executed in parallel (possibly changing the instruction ordering), as this would affect the final value of A.

Data Dependency Problem

The major problem of executing multiple instructions in a scalar program is the handling of data dependencies. If data dependencies are not effectively handled, it is difficult to achieve an execution rate of more than one instruction per clock cycle.

Terminologies in Parallel Computing

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Supercomputing / High Performance Computing (HPC) | Using the world’s fastest and largest computers to solve large problems |

| Node | A standalone “computer in a box” that can be networked together to comprise a supercomputer |

| CPU / Socket / Processor / Core | CPU (Central Processing Unit) was a singular execution component for a computer. Multiple CPUs were incorporated into a node, and individual CPUs were subdivided into multiple “cores.” CPUs with multiple cores are sometimes called “sockets” (vendor dependent). A node with multiple CPUs may contain multiple cores. |

| Task | A logically discrete section of computational work, typically a program or program-like set of instructions that is executed by a processor |

| Parallel tasks | A task that can be executed by multiple processors safely, yielding correct results |

| Serial execution | Execution of a program sequentially, one statement at a time, often on a single processor machine. Virtually all parallel tasks have sections of a parallel program that must be executed serially. |

| Parallel Execution | Execution of a program by more than one task, with each task being able to execute the same or different statements at the same moment in time |

| Pipelining | Breaking a task into steps performed by different processor units, with inputs streaming through, much like an assembly line; a type of parallel computing |

| Symmetric MultiProcessor (SMP) | Hardware architecture where multiple processors share a single address space and access to all resources, known as shared memory computing |

| Distributed Memory | Hardware: network-based memory access for physical memory that is not common; Programming model: tasks can only logically “see” local machine memory and must use communications to access memory on other machines where other tasks are executing |

| Shared Memory | Hardware: describes a computer architecture where all processors have direct access to common physical memory; Programming model: parallel tasks all have the same “picture” of memory and can directly address and access the same logical memory locations regardless of where the physical memory exists |

| Communications | Exchange of data; can occur through shared memory buses or over a network |

| Granularity | Qualitative measure of the ratio of computation to communication. Can be coarse (relatively large amounts of computational work done between communication events) or fine (relatively small amounts of computational work done between communication events) |

| Scalability | Refers to a parallel system’s (hardware and/or software) ability to demonstrate a proportionate increase in parallel speedup with the addition of more processors |

| Parallel Overhead | The amount of time required to coordinate parallel tasks |

| Massively Parallel | Hardware comprising a given parallel system with many processors |

| Speed | The time it takes the program to execute |

Performance Measurement

Amdahl’s Law

Amdahl’s Law states that potential program speedup is defined by the fraction of code (P) that can be parallelized:

\[\text{speedup} = \frac{1}{1 - P}\]- If none of the code can be parallelized, P = 0, and the speedup = 1 (no speedup).

- If all of the code is parallelized, P = 1, and the speedup is infinite (in theory).

- If 50% of the code can be parallelized, the maximum speedup = 2, meaning the code will run twice as fast.

Introducing the number of processors performing the parallel fraction of work, the relationship can be modeled by:

\[\text{speedup} = \frac{1}{\frac{P + S}{N}}\]Where P = parallel fraction, N = number of processors, and S = serial fraction.

Here’s a table illustrating speedup calculated using the formula above for different values of P:

| N | P = 0.50 | P = 0.90 | P = 0.99 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1.82 | 5.26 | 9.17 |

| 100 | 1.98 | 9.17 | 50.25 |

| 1000 | 1.99 | 9.91 | 90.99 |

| 10000 | 1.99 | 9.91 | 99.02 |

Complexity

- In general, parallel applications are much more complex than corresponding serial applications, perhaps an order of magnitude. Not only do you have multiple instruction streams executing at the same time, but you also have data flowing between them.

- The costs of complexity are measured in programmer time in virtually every aspect of the software development cycle:

- Design

- Coding

- Debugging

- Tuning

- Maintenance

- Adhering to “good” software development practices is essential when working with parallel applications, especially if somebody besides you will have to work with the software.